Hydrogen sulfide odor. Why my wine is smelling bad?

Written by torosidiswine

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a thiol of very high volatility with a very low concentration in which its odor is perceived, an odor reminiscent of that of a spoiled egg. The presence of hydrogen sulphide in must and wine can be due to many causes (Monk 1986). Those related to yeasts and nitrogen are commented on below.

It has been well documented that hydrogen sulfide is metabolically formed by yeasts either from inorganic sulfur compounds, such as sulphites and sulfates, or from organic sulfur compounds such as cysteine and glutathione (Rankine 1963, Eschenbruch 1974, 1978, Schiitz and Kunkee 1977, Monk 1986, Henschke and Jiranek 1993, Rauhut 1993, Jiranek et al. 1995b, Hallinan et al. 1999, Spiropoulis et al. 2000).

Hydrogen sulfide is usually synthesized to meet the increased metabolic needs of yeasts in organic sulfur compounds, such as those that occur during their growth phase.

Some strains, however, appear to form irregular amounts of hydrogen sulfide and may represent metabolic errors at least for the environment that characterizes the wine (Jiranek et al. 1995b, Spiropoulis et al. 2000).

Must is usually deficient in organic sulphur compounds (less than 10 mg/l cysteine and methionine). The lack of organic sulfur compounds in must stimulates the synthesis of organic sulfur compounds in yeasts from inorganic sources which are usually found in surplus in the must (Henschke and Jiranek 1991, Hallinan et al. 1999). Thus, hydrogen sulfide is an intermediate product of metabolism during the reduction of sulfates or sulphites necessary for the synthesis of organic sulfur compounds (Rauhut 1993).

When these reactions evolve in the presence of the appropriate amount of nitrogen, hydrogen sulfide is removed, with the formation of organic sulfur compounds (Ono et al. 1999). However, under certain conditions, when insufficient or inappropriate sources of nitrogen are available, free hydrogen sulfide can accumulate inside the cell and diffuse into the fermented must (Henschke and Jiranek 1991).

The hydrogen sulfide formed from the beginning and until the middle of the alcoholic fermentation of the must is associated with the growth of yeasts, and its formation usually responds to the addition of nutrients, in particular diammonium phosphate (Henschke and Jiranek 1991, Jiranek et al. 1995b).

The yeast strain used, the source of sulfur, the composition and concentration of nitrogen in the fermented medium are among the factors affecting the production of hydrogen sulfide (Spiropoulis et al. 2000). Research conducted by different methods shows that yeast strains exhibit great variability in their ability to produce hydrogen sulfide, thus making the yeast strain as the most important factor determining hydrogen sulfide production (Rankine 1968a, Eschenbruch et al. 1978, Thornton and Bunker 1989, Thomas et al. 1993, Giudici and Kunkee 1994, Jiranek et al. 1995c, Spiropoulis et al. 2000, Mendes-Ferreira et al. 2002).

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a thiol of very high volatility with a very low concentration in which its odor is perceived, an odor reminiscent of that of a spoiled egg. The presence of hydrogen sulphide in must and wine can be due to many causes (Monk 1986).

Laboratory studies have shown that for a strain that responds to nitrogen addition during alcoholic fermentation, an amino acid’s ability to regulate hydrogen sulfide production is related to its effectiveness as a nitrogen source, although there are several notable exceptions (Jiranek et al. 1995b).

As ammonials restrict the expression of the Met10 gene, which is responsible for encoding the α-subgroup of sulfite reductase (Hansen et al. 1994), it is not surprising that diammonium phosphate is widely used in practice to control hydrogen sulfide production, but it is not always effective.

Henschke and Jiranek (1991) identified a second phase of hydrogen sulfide production associated with the final stages of alcoholic fermentation. In this phase there was virtually no response to the addition of diammonium phosphate, although in some cases diammonium phosphate seems to stimulate the production of hydrogen sulfide when combined with aeration (Thomas et al. 1993, Henschke and de Kluis 1995).

Although recent research improves our knowledge on sulphur metabolism in yeasts, particularly on the subject of hydrogen sulphide production, the use of selected strains remains the most useful tool to limit hydrogen sulphide production during winemaking.

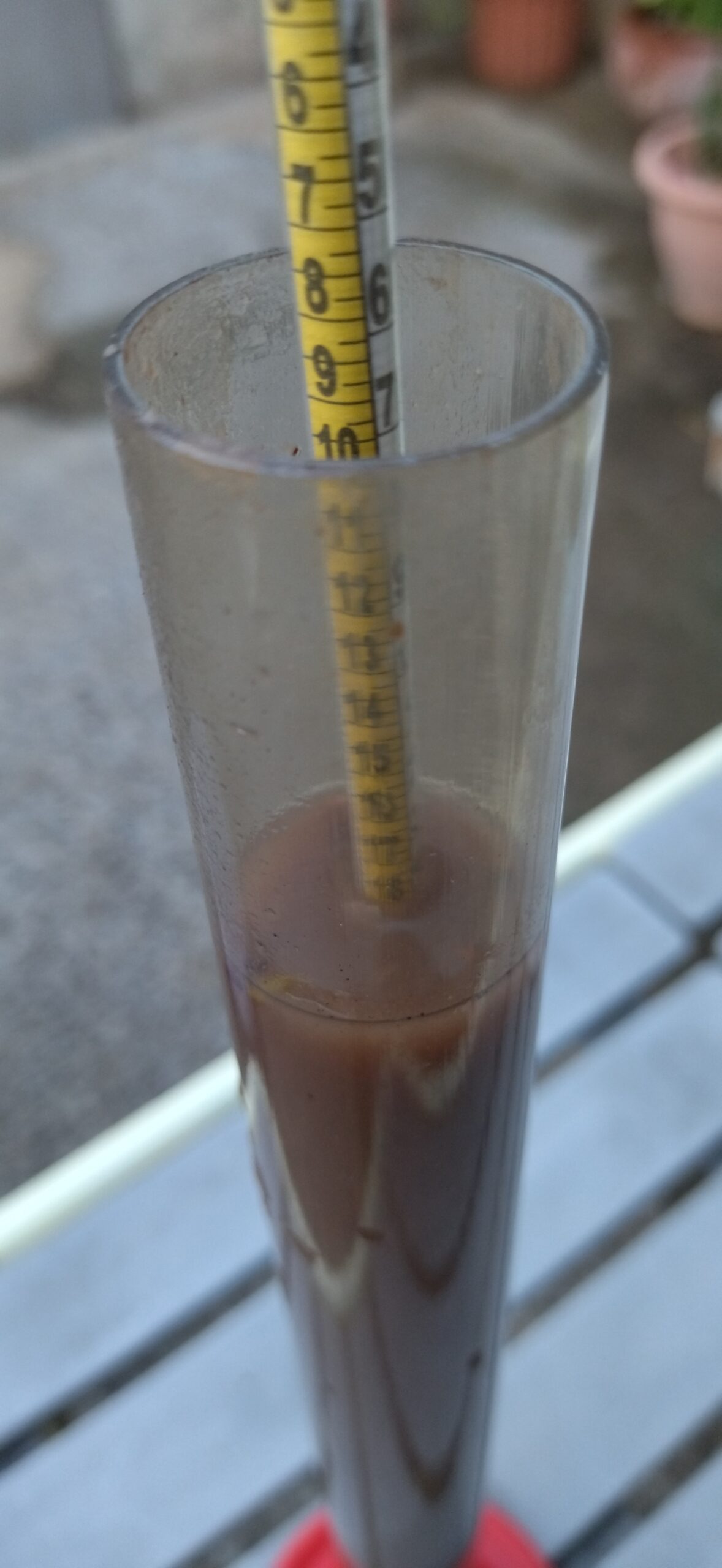

As the production of hydrogen sulphide during the alcoholic fermentation of must has many causes, the measurement of nitrogen assimilability by yeasts in the must and the addition of nitrogen (e.g. diammonium phosphate) continue to be the best approach to control the actual production of hydrogen sulphide at the beginning and up to the middle of alcoholic fermentation. Only when the production of hydrogen sulphide fails to be regulated by the addition of nitrogen should other options be sought.

Πηγή : Bell S-J and P.A. Henschke , 2005. Implications of nitrogen nutrition for grapes , fermentation and wine. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research 11 , 242-295.

Our Wines

Shop

Related Articles

Related

Compulsory declarations of wine sector

All operators active in wine production, bottling of wine products, marketing of wine products before the wine-making stage and marketing of bottled wines, with the exception of retail businesses, must register in the register of enterprises in the wine sector....

Wine instability. Protein haze

Nitrogen compounds in wine include proteins. Proteins contribute significantly to the concentration of nitrogen not digestible by yeasts in must and wine. They are the most common cause of clouding in white wines. Protein blurring is a problem of serious economic...

Nitrogen vineyard nutrition affects yeast assimilable nitrogen

The addition of nitrogen to vine plants increases the concentration of nitrogen in the rail. Many components of the rail that contribute to the taste and aroma of wine are affected by the addition of nitrogen directly or indirectly. Thus, changes in the concentration...